(or why restrictions are the secret of artistic style)

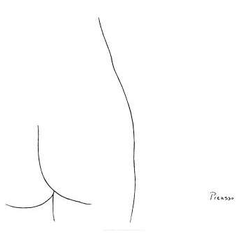

Why do artists sometimes draw using pen and ink when they could have used colored paint instead? Why would they constrain their expressive power and settle for black lines on white paper when they could create a full spectrum of colors and shades using oil or acrylic paints? They do so not just because it is quicker to draw with ink, but because they enjoy the challenge of creating their desired effects under these constraints – the challenge of creating the effects of solid forms and tone just with black lines. Artists always deliberately constrain themselves in terms of medium and style, and then try to get the most out of those constrained conditions. The challenge of creating under constrained conditions is a major factor that drives artists. The way I look at it, it is also at the core of what we often call personal style that distinguishes one artist from another.

Why do artists sometimes draw using pen and ink when they could have used colored paint instead? Why would they constrain their expressive power and settle for black lines on white paper when they could create a full spectrum of colors and shades using oil or acrylic paints? They do so not just because it is quicker to draw with ink, but because they enjoy the challenge of creating their desired effects under these constraints – the challenge of creating the effects of solid forms and tone just with black lines. Artists always deliberately constrain themselves in terms of medium and style, and then try to get the most out of those constrained conditions. The challenge of creating under constrained conditions is a major factor that drives artists. The way I look at it, it is also at the core of what we often call personal style that distinguishes one artist from another.

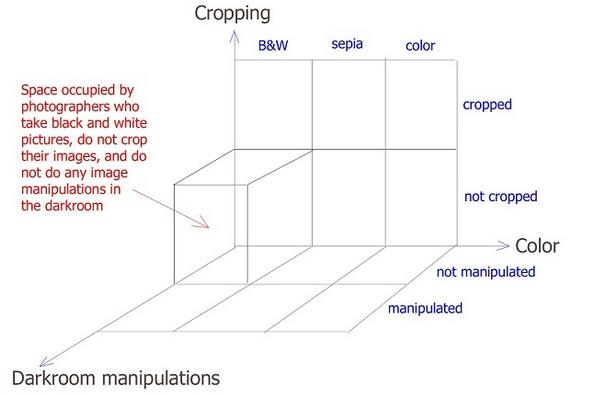

Kodachrome color film was introduced in the 1930s, but even today there are many photographers who photograph in black and white. The challenge here is to intentionally impose a constraint, that of not capturing the colors, and to create a great image just in tones of grey. There are many photographers, including the famous Henri Cartier-Bresson, who would never crop their photographs and compose entirely in the view finder. There are photographers who only capture scenes that are naturally created while there are others who almost exclusively photograph subjects that are carefully arranged. In the digital era, there are artists who use digital editing techniques to manipulate their images and there are others who would never change the captured image using image-manipulation techniques. All of these variations can be seen as a series of independent decisions – color or black-and-white, cropped or not, natural or staged, image manipulated or not. Any combination of these factors defines the style a photographer may chose to adopt. Of course not all combinations are equally common or meaningful. It is unlikely that a photographer would chose to use digital image manipulation techniques, but would be resistant to cropping an image.

The same can be said about other forms of visual art. On one hand the medium used implies a certain constraint. An artist chooses that medium where the constraints appeal to the artist’s needs and sensibilities. Then, on top of the constraints implied by the medium, the artist usually applies other stylistic constraints. For example, the early impressionist painters adopted a set of stylistic constraints to mostly paint with short brush strokes with vivid colors. The colors were not blended on the canvas itself, but rather the blending happened in the viewer’s eyes. They also decided to use everyday life as their subjects as opposed to biblical or mythological themes. Of course the specific stylistic constraints were not picked arbitrarily, but were guided by practical and aesthetic needs.

Very often, once an individual artist settles on a set of constraints, they stay with it for a while, challenging themselves to create interesting art and communicating whatever they are trying to communicate, while not violating the self-imposed constraints. Sometimes we see an artist playing with the constraints, relaxing here, adding another there, till they are happy with their choice. In traditional terms we would say that the artist, during that phase, was searching for his style. Once a style is established, and if it is slightly different from all other artists, then that becomes the signature of that individual, and we recognize their work at once. Almost all artists are in search for their personal set of constraints, but not everyone succeeds in finding one that is unique and interesting at the same time. Once they do discover a promising style, they have to prove to themselves and others that the unique set of constraints are not only good for creating a small number of pieces, but that it has the potential of creating a very large collection of works. When the discovered style is really fertile, other artists start adopting variations of it, and we call that style an “art movement”.

For example Picasso, at some point in his career, discovered a style, or a set of constraints, that is known as cubism. Here he broke the image plane into smaller flat surfaces, and captured the subject from various angles and perspectives into these flat facets. After discovering this style, he did not stop using it after one two paintings, but continued exploring the expressive power through dozens of paintings. In this case the style was so fertile that many other painters started using the basic set of constraints and started creating their own version of cubist paintings, thus creating a new art movement. Out of these other cubists, the ones we still remember are the ones who just didn’t use Picasso’s set of constraints, but added some of their own, to create their own style variation.

For many artists, after they discover a fruitful style, continue to explore that till the end of their career. However, for the truly creative artists, they create a style; explore it enough to establish its power, and then move on to totally new sets of constraints. Picasso, for example, was creative and restless enough to change his style drastically throughout his life.

Of course, not all constraints are equally fruitful. Consider a painter that decides to explore a style where the only colors he would use are black and white, and the only shape is a circle of a fixed diameter. You can easily imagine a set of interesting visual paintings coming out of it – white canvases with black circles on them, in various positions. One can possibly create a reasonable body of work under these constraints. However, it is hard to imagine that one can spend a lifetime exploring this very limited space, or that other artists may pick it up and practice variations of this style.

Very often, once an individual artist settles on a set of constraints, they stay with it for a while, challenging themselves to create interesting art and communicating whatever they are trying to communicate, while not violating the self-imposed constraints. Sometimes we see an artist playing with the constraints, relaxing here, adding another there, till they are happy with their choice. In traditional terms we would say that the artist, during that phase, was searching for his style. Once a style is established, and if it is slightly different from all other artists, then that becomes the signature of that individual, and we recognize their work at once. Almost all artists are in search for their personal set of constraints, but not everyone succeeds in finding one that is unique and interesting at the same time. Once they do discover a promising style, they have to prove to themselves and others that the unique set of constraints are not only good for creating a small number of pieces, but that it has the potential of creating a very large collection of works. When the discovered style is really fertile, other artists start adopting variations of it, and we call that style an “art movement”.

For example Picasso, at some point in his career, discovered a style, or a set of constraints, that is known as cubism. Here he broke the image plane into smaller flat surfaces, and captured the subject from various angles and perspectives into these flat facets. After discovering this style, he did not stop using it after one two paintings, but continued exploring the expressive power through dozens of paintings. In this case the style was so fertile that many other painters started using the basic set of constraints and started creating their own version of cubist paintings, thus creating a new art movement. Out of these other cubists, the ones we still remember are the ones who just didn’t use Picasso’s set of constraints, but added some of their own, to create their own style variation.

For many artists, after they discover a fruitful style, continue to explore that till the end of their career. However, for the truly creative artists, they create a style; explore it enough to establish its power, and then move on to totally new sets of constraints. Picasso, for example, was creative and restless enough to change his style drastically throughout his life.

Of course, not all constraints are equally fruitful. Consider a painter that decides to explore a style where the only colors he would use are black and white, and the only shape is a circle of a fixed diameter. You can easily imagine a set of interesting visual paintings coming out of it – white canvases with black circles on them, in various positions. One can possibly create a reasonable body of work under these constraints. However, it is hard to imagine that one can spend a lifetime exploring this very limited space, or that other artists may pick it up and practice variations of this style.

In the popular website called Instagram, there are many small groups who participate in a daily game. The administrator of the group posts a new photograph every day. The group participants then take this single photograph, and they modify and augment it any way they want, mostly using digital image manipulation techniques. The final results are amazingly diverse, and sometimes very creative. In this case the constraint is fairly severe, as each piece must start with the same single photograph, arbitrarily picked by the group administrator. A severe constraint like this is what makes the game challenging for the participants, but the severity and the arbitrariness of the constraint is also what makes the final results, no matter how creative, artistically limited.

One way of visualizing all of this is to imagine a vast space that represents all possible stylistic variations. Unlike the three-dimensional space we live in, this space has many more dimensions than three. Taking the photography example from the beginning of this article, one dimension would be for color, where the different points on this axis would represent black-and-white, sepia, color, etc. The next dimension would be whether cropping is allowed or not. The third dimension would be whether darkroom manipulations are allowed or not. With these three dimensions we can imaging our usual 3-D space, where a photographer like Cartier Bresson would occupy the sub-space defined by the values B&W, no-cropping, and no-darkroom manipulation. Now, if we add another dimension to it for whether the images are of naturally occurring subjects or carefully arranged objects then we can no longer visualize it as a conventional space, because our real world has only three dimensions. However, in our imagination we can imagine a space that has 4 dimension, or 5, or 100,000. Mathematicians do that all the time, and there are no limits to the number of dimensions one can imagine. With that in mind, now we can add other dimensions such as the recording medium – film or digital. We can add another dimension for the degree of digital manipulation of the captured image that is allowed.

Imagine doing the same for all of visual arts. That is, we look at various arts and keep adding new dimensions to this art-space. Once we have an adequate number of dimensions describing everything we can imagine, we can then take a phase of an artist and see which specific constraints he or she used. The net result will be a tiny subspace in this huge volume.

Every artist is looking for an empty spot in this space to claim his or her own. Some are lucky enough to discover entirely new dimensions and thus expand the space itself. Others may discover their own constraints, or even their own dimensions, but the resulting space may be uninteresting, and we would soon forget them. Others may create a new space, but the recognition of its uniqueness and beauty may take decades to be accepted.

Given this perspective, I personally find it very rewarding to use it in seeing other people’s work or doing my own. When I am looking at a body of work by an artist, I try to consciously think of the constraints this artist applied on their own self. I try to enumerate and verbalize the set of constraints. One cannot do that by looking at a single work done by an artist, but a whole body of work because the constraints may look too tight and specific when applied to a single work, but they start generalizing and relaxing when a whole collection comes into view. If I succeed in doing so, then it becomes easier for me to relate this artist’s work with work done by others. Very often, a piece that may look beautiful, ends up occupying a crowded space in the art-space, thus becoming nothing more than just another example of a style that has already been well explored. At other times I would be surprised and excited by a work because I will realize the space it is occupying is not at all crowded. Of course art appreciation is ultimately an emotional process, and I am not suggesting we need to make it entirely analytical, but I believe we already use a similar technique, even though we may not be aware of it, when judging the value of a piece of art.

I am imagining this cavernous art-space. I see a huge block out there occupied by Picasso’s cubism. I see other blocks of space scattered around with Picasso’s name on them. I see blocks, big and small with artists I have known. I am looking for a tiny space to call my own, but it is not easy. There are millions of artists milling around, looking for the same. Any open space that is here now is gone in a minute. It is the grand artistic land grab. The only good news is that the space is constantly expanding. New dimensions are getting added. My best chance of finding a space is by adding a useful dimension or two and creating my own space. I am snooping around at the edges for signs where new dimensions can be added – my eyes are wide open.

Older Comments (8)

1. Jagriti Ruparel said on 1/19/13 - 10:03PM

Interesting read on how art forms and artists use 'constraints' to define and find their own space! In everyday life we do the same and with the same intensity.

2. Dulali Nag said on 1/20/13 - 01:56AM

While reading through the piece and before coming to Jagriti's comments, I was thinking exactly what she has expressed. That every creative act, no matter how trivial, becomes itself by creating a space for itself by choosing certain elements from an available array of elements in the total range of a space. The chosen elements are the constraints, or the parameters or the turf or whatever you might want to call it. What Kunal has successfully captured through his focus on visual art is a universally true strategic movement that humans deploy whenever they feel compelled to express something that calls for a new style/language/tune/stroke.

3. Kunal Sen said on 1/20/13 - 07:44AM

Jagriti and Dulali, I agree with you that this point of view could be extended to other forms of creative expression, and I also consider just the act of living our lives a complex form of creative act. However, what I wrote is the technique I use to understand visual arts, and I didn't want to take the risk of over-generalization without more thought. I am sure many would find even this narrow application of the idea objectionable.

4. Nick Markos said on 1/20/13 - 08:31AM

Wonderfully articulated, and great ideas to think about, for any type of artist (visual, musical, etc.). Thank you for sharing this, Kunal!

5. Arjun Gupta said on 1/20/13 - 10:49AM

Kunal, I spent the 1/2 hour drafting a response to your post but the comment form wouldn't allow me to submit - probably because it took offense to some of the Italian art terms I used! Here's what I was able to salvage from my lengthy response: More problematic is the idea that constraint is linked to a capacity for expression, or the broader notion in this post that there is an equivalence or a priori relationship between constraint and style. Can we say with certainty that Picasso "discovered a style, or set of constraints, that is known as cubism"? I'm not so sure. Was Picasso even concerned about expression? His own emotional or psychological state? A comment on the world and the times he lived in? Perhaps. Demoiselles D'Avignon is an expressive painting. The mask-like faces of the prostitutes, the confusing spatial relations, the confrontational postures, make us feel something, but what we feel is not necessarily what its audience felt at the time of its creation. Is it a painting about the primitivism in man (or woman)? About Picasso's relationship to women? Is it intended to antagonize the arbiters of culture? Is Picasso working out early cubist problems of space and form? It may be all of these things, but it is not just a matter of style in the sense of pictorial outcomes (cubism) and formal decisions (facets). There are a host of other, equally compelling factors that drive Picasso's creative purpose. My point is that the social history of art is a critical dimension in considering style and expression. Considerations of medium and formal analysis can only take one so far... Admittedly my two cents from an art historical perspective and not from the practitioner's point of view!

6. Arjun Gupta said on 1/20/13 - 10:53AM

Kunal, I tried leaving a comment but went over the 1000 word limit and used Italian art terms that were deemed unacceptable by the comment function! There are points I agree and disagree with in your post, but until I can express myself in my own style, I'm afraid my comment will go unread!

7. Kunal Sen said on 1/20/13 - 11:00AM

Arjun, I think I could salvage this from your "lost" comment -- you wrote ... "I think it's useful to separate photography from the rest of the visual arts in this discussion - for reasons that would take too long to go into here... I agree "constraints" are challenging and motivating to some artists, but the medium of pen and ink, or more broadly speaking, black and white, should not necessarily be considered a constraint, nor is style pegged to a value of expression (as opposed to representation). But let's take on the first assumption before we address the second. Does black and white constrain expression? What are some examples of that contradict this suggestion? The Expressionism of pre-war Germany is most powerful in black and white for the stark contrasts it affords, the long tradition of monochrome ink landscape painting of China and Japan held philosophical and religious underpinnings that aren't always as evident in works of color form those traditions, the etchings of the Northern Renaissance and the foundational practice of drawing in the Italian Renaissance tradition are probably the easiest places to start. But I offer up the other examples to emphasize the different developmental causes and diversity in visual culture - modern and pre-modern, Eastern and Western - that need consideration when addressing the notion of black and white and expression. The tradition of drawing/etching in the Northern and Italian Renaissance goes beyond mere design and focus on composition, encompassing other techniques that translate into oil and fresco painting: sfumato, chiaroscuro etc. These are principally modeling techniques to show volume, density, naturalism etc. In other words, they are about more than composition (traditionally ascribed to drawings of the Old Masters), but also about resolving formal pictorial issues. In this context, drawing and etching are not so much constraining media as they are useful for the artists' purpose. For Durer and Schongauer etchings provided market opportunities and the ability to disseminate their ideas. For Italian Renaissance painters, they provided the means to work out pictorial problems that could be applied to larger, complex paintings. So one important consideration is the role that the media plays beyond expression. More problematic is the idea that constraint is linked to a capacity for expression, or the broader notion in this post that there is an equivalence or a priori relationship between constraint and style. Can we say with certainty that Picasso "discovered a style, or set of constraints, that is known as cubism"? I'm not so sure. Was Picasso even concerned about expression? His own emotional or psychological state? A comment on the world and the times he lived in? Perhaps. Demoiselles D'Avignon is an expressive painting. The mask-like faces of the prostitutes, the confusing spatial relations, the confrontational postures, make us feel something, but what we feel is not necessarily what its audience felt at the time of its creation. Is it a painting about the primitivism in man (or woman)? About Picasso's relationship to women? Is it intended to antagonize the arbiters of culture? Is Picasso working out early cubist problems of space and form? It may be all of these things, but it is not just a matter of style in the sense of pictorial outcomes (cubism) and formal decisions (facets). There are a host of other, equally compelling factors that drive Picasso's creative purpose. My point is that the social history of art is a critical dimension in considering style and expression. Considerations of medium and formal analysis can only take one so far... Admittedly my two cents from an art historical perspective and not from the practitioner's point of view!"

8. Kunal Sen said on 1/22/13 - 10:43PM

Arjun, thank you for your thoughtful comments. I am flattered by the very fact that a professional art historian like yourself even read my piece, and then spent time to write a response. I am really sorry that the blog software misbehaved when you tried to submit. The platform I use is really very poor, and I should move to something else. Let me start with the obvious fact that I am no art historian, and my observations are that of a person who loves art, mixed with the fact that my training is in Science, and therefore suffer from a deep compulsion to see patterns in things around me. My focus was just on the formal aspects of style. I definitely don’t claim that artists are primarily driven by a desire to create new formal structures. Social and practical forces shape their creative decisions just as much, if not more. But isn’t it also true that a successful artist also creates a certain distinctive formal style that becomes his or her signature? That’s what allows us to identify the work of a particular artist That is not to say that the artist consciously created the distinctive style just to be different. There are other needs, could be emotional, social, or just practical that prompts them to explore new forms, but in the end they do find a formal style that is distinctive. Consider an artist who paints a new painting, on a brand new subject, but it looks like the work of Van Gogh -- will we pay much attention to it? I think, to be noticed, an artist must establish his own distinctive style or visual language, alongside the content. Regarding the issue of black and white, line drawings, and restrictions – my use of the term “restriction” is not meant to imply a limit on what can be expressed, but strictly as a limiting of the tools that the artist allowed himself to use. Of course, under some circumstances, one can express more with less. A black painting can be more expressive in a given context. During the state of emergency imposed by the central government in India, when press censorship became rather common, the most expressive editorial I saw in a left-wing magazine was a blank white page. So, I have no doubt that limiting your tools does not necessarily mean restricting your ability to communicate, but what I am talking about is the fact that an artist, at a formal level, could make a conscious decision to stick to simple lines to depict volume and space. That to me is interesting, and I am trying to see all formal styles as imposing one type of restriction on or another on oneself.

Every artist is looking for an empty spot in this space to claim his or her own. Some are lucky enough to discover entirely new dimensions and thus expand the space itself. Others may discover their own constraints, or even their own dimensions, but the resulting space may be uninteresting, and we would soon forget them. Others may create a new space, but the recognition of its uniqueness and beauty may take decades to be accepted.

Given this perspective, I personally find it very rewarding to use it in seeing other people’s work or doing my own. When I am looking at a body of work by an artist, I try to consciously think of the constraints this artist applied on their own self. I try to enumerate and verbalize the set of constraints. One cannot do that by looking at a single work done by an artist, but a whole body of work because the constraints may look too tight and specific when applied to a single work, but they start generalizing and relaxing when a whole collection comes into view. If I succeed in doing so, then it becomes easier for me to relate this artist’s work with work done by others. Very often, a piece that may look beautiful, ends up occupying a crowded space in the art-space, thus becoming nothing more than just another example of a style that has already been well explored. At other times I would be surprised and excited by a work because I will realize the space it is occupying is not at all crowded. Of course art appreciation is ultimately an emotional process, and I am not suggesting we need to make it entirely analytical, but I believe we already use a similar technique, even though we may not be aware of it, when judging the value of a piece of art.

I am imagining this cavernous art-space. I see a huge block out there occupied by Picasso’s cubism. I see other blocks of space scattered around with Picasso’s name on them. I see blocks, big and small with artists I have known. I am looking for a tiny space to call my own, but it is not easy. There are millions of artists milling around, looking for the same. Any open space that is here now is gone in a minute. It is the grand artistic land grab. The only good news is that the space is constantly expanding. New dimensions are getting added. My best chance of finding a space is by adding a useful dimension or two and creating my own space. I am snooping around at the edges for signs where new dimensions can be added – my eyes are wide open.

Older Comments (8)

1. Jagriti Ruparel said on 1/19/13 - 10:03PM

Interesting read on how art forms and artists use 'constraints' to define and find their own space! In everyday life we do the same and with the same intensity.

2. Dulali Nag said on 1/20/13 - 01:56AM

While reading through the piece and before coming to Jagriti's comments, I was thinking exactly what she has expressed. That every creative act, no matter how trivial, becomes itself by creating a space for itself by choosing certain elements from an available array of elements in the total range of a space. The chosen elements are the constraints, or the parameters or the turf or whatever you might want to call it. What Kunal has successfully captured through his focus on visual art is a universally true strategic movement that humans deploy whenever they feel compelled to express something that calls for a new style/language/tune/stroke.

3. Kunal Sen said on 1/20/13 - 07:44AM

Jagriti and Dulali, I agree with you that this point of view could be extended to other forms of creative expression, and I also consider just the act of living our lives a complex form of creative act. However, what I wrote is the technique I use to understand visual arts, and I didn't want to take the risk of over-generalization without more thought. I am sure many would find even this narrow application of the idea objectionable.

4. Nick Markos said on 1/20/13 - 08:31AM

Wonderfully articulated, and great ideas to think about, for any type of artist (visual, musical, etc.). Thank you for sharing this, Kunal!

5. Arjun Gupta said on 1/20/13 - 10:49AM

Kunal, I spent the 1/2 hour drafting a response to your post but the comment form wouldn't allow me to submit - probably because it took offense to some of the Italian art terms I used! Here's what I was able to salvage from my lengthy response: More problematic is the idea that constraint is linked to a capacity for expression, or the broader notion in this post that there is an equivalence or a priori relationship between constraint and style. Can we say with certainty that Picasso "discovered a style, or set of constraints, that is known as cubism"? I'm not so sure. Was Picasso even concerned about expression? His own emotional or psychological state? A comment on the world and the times he lived in? Perhaps. Demoiselles D'Avignon is an expressive painting. The mask-like faces of the prostitutes, the confusing spatial relations, the confrontational postures, make us feel something, but what we feel is not necessarily what its audience felt at the time of its creation. Is it a painting about the primitivism in man (or woman)? About Picasso's relationship to women? Is it intended to antagonize the arbiters of culture? Is Picasso working out early cubist problems of space and form? It may be all of these things, but it is not just a matter of style in the sense of pictorial outcomes (cubism) and formal decisions (facets). There are a host of other, equally compelling factors that drive Picasso's creative purpose. My point is that the social history of art is a critical dimension in considering style and expression. Considerations of medium and formal analysis can only take one so far... Admittedly my two cents from an art historical perspective and not from the practitioner's point of view!

6. Arjun Gupta said on 1/20/13 - 10:53AM

Kunal, I tried leaving a comment but went over the 1000 word limit and used Italian art terms that were deemed unacceptable by the comment function! There are points I agree and disagree with in your post, but until I can express myself in my own style, I'm afraid my comment will go unread!

7. Kunal Sen said on 1/20/13 - 11:00AM

Arjun, I think I could salvage this from your "lost" comment -- you wrote ... "I think it's useful to separate photography from the rest of the visual arts in this discussion - for reasons that would take too long to go into here... I agree "constraints" are challenging and motivating to some artists, but the medium of pen and ink, or more broadly speaking, black and white, should not necessarily be considered a constraint, nor is style pegged to a value of expression (as opposed to representation). But let's take on the first assumption before we address the second. Does black and white constrain expression? What are some examples of that contradict this suggestion? The Expressionism of pre-war Germany is most powerful in black and white for the stark contrasts it affords, the long tradition of monochrome ink landscape painting of China and Japan held philosophical and religious underpinnings that aren't always as evident in works of color form those traditions, the etchings of the Northern Renaissance and the foundational practice of drawing in the Italian Renaissance tradition are probably the easiest places to start. But I offer up the other examples to emphasize the different developmental causes and diversity in visual culture - modern and pre-modern, Eastern and Western - that need consideration when addressing the notion of black and white and expression. The tradition of drawing/etching in the Northern and Italian Renaissance goes beyond mere design and focus on composition, encompassing other techniques that translate into oil and fresco painting: sfumato, chiaroscuro etc. These are principally modeling techniques to show volume, density, naturalism etc. In other words, they are about more than composition (traditionally ascribed to drawings of the Old Masters), but also about resolving formal pictorial issues. In this context, drawing and etching are not so much constraining media as they are useful for the artists' purpose. For Durer and Schongauer etchings provided market opportunities and the ability to disseminate their ideas. For Italian Renaissance painters, they provided the means to work out pictorial problems that could be applied to larger, complex paintings. So one important consideration is the role that the media plays beyond expression. More problematic is the idea that constraint is linked to a capacity for expression, or the broader notion in this post that there is an equivalence or a priori relationship between constraint and style. Can we say with certainty that Picasso "discovered a style, or set of constraints, that is known as cubism"? I'm not so sure. Was Picasso even concerned about expression? His own emotional or psychological state? A comment on the world and the times he lived in? Perhaps. Demoiselles D'Avignon is an expressive painting. The mask-like faces of the prostitutes, the confusing spatial relations, the confrontational postures, make us feel something, but what we feel is not necessarily what its audience felt at the time of its creation. Is it a painting about the primitivism in man (or woman)? About Picasso's relationship to women? Is it intended to antagonize the arbiters of culture? Is Picasso working out early cubist problems of space and form? It may be all of these things, but it is not just a matter of style in the sense of pictorial outcomes (cubism) and formal decisions (facets). There are a host of other, equally compelling factors that drive Picasso's creative purpose. My point is that the social history of art is a critical dimension in considering style and expression. Considerations of medium and formal analysis can only take one so far... Admittedly my two cents from an art historical perspective and not from the practitioner's point of view!"

8. Kunal Sen said on 1/22/13 - 10:43PM

Arjun, thank you for your thoughtful comments. I am flattered by the very fact that a professional art historian like yourself even read my piece, and then spent time to write a response. I am really sorry that the blog software misbehaved when you tried to submit. The platform I use is really very poor, and I should move to something else. Let me start with the obvious fact that I am no art historian, and my observations are that of a person who loves art, mixed with the fact that my training is in Science, and therefore suffer from a deep compulsion to see patterns in things around me. My focus was just on the formal aspects of style. I definitely don’t claim that artists are primarily driven by a desire to create new formal structures. Social and practical forces shape their creative decisions just as much, if not more. But isn’t it also true that a successful artist also creates a certain distinctive formal style that becomes his or her signature? That’s what allows us to identify the work of a particular artist That is not to say that the artist consciously created the distinctive style just to be different. There are other needs, could be emotional, social, or just practical that prompts them to explore new forms, but in the end they do find a formal style that is distinctive. Consider an artist who paints a new painting, on a brand new subject, but it looks like the work of Van Gogh -- will we pay much attention to it? I think, to be noticed, an artist must establish his own distinctive style or visual language, alongside the content. Regarding the issue of black and white, line drawings, and restrictions – my use of the term “restriction” is not meant to imply a limit on what can be expressed, but strictly as a limiting of the tools that the artist allowed himself to use. Of course, under some circumstances, one can express more with less. A black painting can be more expressive in a given context. During the state of emergency imposed by the central government in India, when press censorship became rather common, the most expressive editorial I saw in a left-wing magazine was a blank white page. So, I have no doubt that limiting your tools does not necessarily mean restricting your ability to communicate, but what I am talking about is the fact that an artist, at a formal level, could make a conscious decision to stick to simple lines to depict volume and space. That to me is interesting, and I am trying to see all formal styles as imposing one type of restriction on or another on oneself.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed